1-Page Summary

Expecting Better contains a wealth of information on conception, pregnancy, and labor. Here are some of the most memorable points, especially when they contradict common wisdom.

Conception

Your chances of getting pregnant decline with age. Chance of conception in a month is 24% at age 25; 21% at age 30; 16% at age 35; 7% at age 40; and 3% at age 45.

In terms of timing sex, it’s pretty much impossible to get pregnant outside of a 6-day window before the day of ovulation. That’s because the egg only survives for 24 hours after release, so the sperm have to be waiting in the Fallopian tube to greet the egg. Luckily, sperm live up to 5 days. Therefore, the best chance of conception happens the day before or the day of ovulation. Conception can still happen up to 5 days before ovulation, with lower chances.

The frequency of sex during this 6-day window does NOT make a difference in chance of conception - it's more important to hit the right day.

There are a variety of ways to track ovulation, including temperature charting and cervical mucus. The most accurate is ovulation sticks, which detect hormones in urine. Of women randomly given access to ovulation detection sticks, 23% got pregnant within 2 months, vs 15% who didn’t have them.

Pregnancy

Risks to Baby

Alcohol: There’s no strong evidence showing 1 drink per day affects child IQ, test scores, or behavior problems. However, this means sipping 1 drink per day, not binge drinking 7 drinks in one night and abstaining the other 6 nights.

Caffeine: It seems safe to have up to 3-4 cups of coffee per day.

Tobacco: Tobacco is not recommended at any time in pregnancy or in life.

Food: Toxoplasmosis and Listeria are the most dangerous infections to the baby. These come from undercooked meats, unwashed produce, and other sporadic outbreaks. Otherwise, for typical foods that may cause illness (from raw eggs, raw fish, shellfish) use your standard caution - your risk of infection aren’t higher when you’re pregnant.

Pharmaceuticals: Many drugs that are probably safe for pregnant women don’t get an explicit clearance from the FDA, because they’re hard to test in randomized controlled trials. Check the full summary for a list of common examples by their FDA category.

Miscarriages

The risk of miscarriage is highest at week 6 (2 weeks after missed period) at 10-15%, then declines rapidly to 2% by week 11.

It’s common to announce after the first trimester (roughly 12 weeks), but the risk of miscarriage decreases substantially by week 9.

These factors increase miscarriage rate: having a previous miscarriage; maternal age; IVF pregnancies.

Prenatal Screening

Many parents want to get prenatal screening to detect chromosomal abnormalities like Down Syndrome. The traditional techniques of amniocentesis and chorionic villi sampling are accurate but have risk of causing miscarriage. There’s a newer noninvasive test, cell-free fetal DNA testing, that has very high accuracy, with both sensitivity and specificity above 99%.

Before getting a screen, it’s useful to consider what you’re going to do based on the news you receive. For some parents, screening may have no point - no matter what they find, they’ll continue with the pregnancy. Then testing would just cause undue anxiety and may be unnecessary.

If you do want a test, then consider what you’ll do if you get a positive or negative result.

Weight Gain

Mothers starting at a normal BMI should aim to gain about 30 pounds over pregnancy. If you deviate, it’s better to err toward more weight gain than too little weight, since complications for low weight babies are much worse.

Some women may undereat in the hopes that they won’t have to take off weight after pregnancy. But 90% of women starting out at normal weight had returned to normal weight by 24 months postpartum.

Labor and Delivery

Birth Timing and Complications

90% of babies are born week 37 and above (“normal term birth”).

Incredibly, a baby born at 22 weeks (a bit over half of the normal pregnancy length of 40 weeks) still has a 23% chance of survival, due to improvements in assistive breathing and other technology.

At week 42, pregnancy is medically induced, due to increased risk of stillbirth.

Some serious complications like placental abruption are mercifully rare, affecting <1% of mothers.

The Delivery

Birth plans are short documents that describe what you want to happen during your birth and what treatments you’re willing to accept in which situations. For instance, you can describe in what conditions you want labor to be induced and how intensely you want the fetus monitored. Oster argues it’s far better to think about hard decisions and articulate your preferences beforehand than to come up with them on the fly.

About 66% of women get epidurals. They don’t show differences in fetal outcomes, but they do increase pushing time, cause longer recovery, and have some minor risks.

Doulas are labor companions who support women throughout the childbirth journey and show lower risk of C-section and use of epidurals. Oster really liked this.

<1% of women in the US have a home birth.

Introduction

Emily Oster is a Harvard-trained economist at Brown University. When she was pregnant, she was dismayed at the quality of pregnancy information. First, clinicians and other mothers seemed to have contradictory ironclad rules for pregnancy. Secondly, and even worse, it wasn’t clear what evidence supported their beliefs, despite their strength of conviction!

For Oster, getting pregnancy advice felt like having a realtor who said that some people don’t like houses with backyards, so they wouldn’t have any houses with backyards on their showing list. Then, when Oster said she actually did like backyards, the realtor would say, “no, you actually don’t. This is the rule.” Obviously this sounds ridiculous - but this is the usual state of pregnancy advice.

Unwilling to take common advice at face value, Oster decided to peruse the medical literature for real data to some of her questions. Was drinking a glass of red wine really all that bad? What’s the best way to arrange for delivery? To her dismay, she found a vast range of study quality (usually varying in sample size and how well the study controlled for confounding factors). But she noticed trends and suggestive data that she’s sharing in this book.

Expecting Better is not generally meant as a prescriptive guide. Rather, just as Oster trains her economics students, you should 1) gather the right data about a decision, 2) weigh your personal costs and benefits, 3) make your personal decision based on all the information you have.

(Shortform note: in this summary, we’ll use “you” as though we’re speaking to the mother.)

Part 1: Conception | Chapters 1-3

Chances of Conception

Contrary to what you learned in high school health class, it’s not that easy to get pregnant. Female fertility peaks in your teens, then decreases gradually from then on, until falling off a cliff around age 45.

In more positive terms, you’re much more likely than not to have a baby if you’re in your 30s.

A study of births at different ages from the 1800s shows that the chance of having children:

- is similar between ages 20 and 35

- women aged 35 to 39 are 90% as likely as the youngest group

- women aged 40-44, 62% as likely

- Women aged 45-49, 14% as likely.

A more modern study of artificial insemination showed that after 12 cycles (months), women under 30 had a pregnancy rate of 75%; women age 31-35, 62%; women over 35, 54%.

(Shortform note: it’s not explained what comprises the 46% of women over 35 who weren’t able to get pregnant after 12 cycles. What fraction of women will get pregnant with more cycles, and what fraction will unfortunately never be able to conceive?)

How Weight Affects Conception

70% of the US is overweight (BMI > 25) and 35% are obese (BMI > 30).

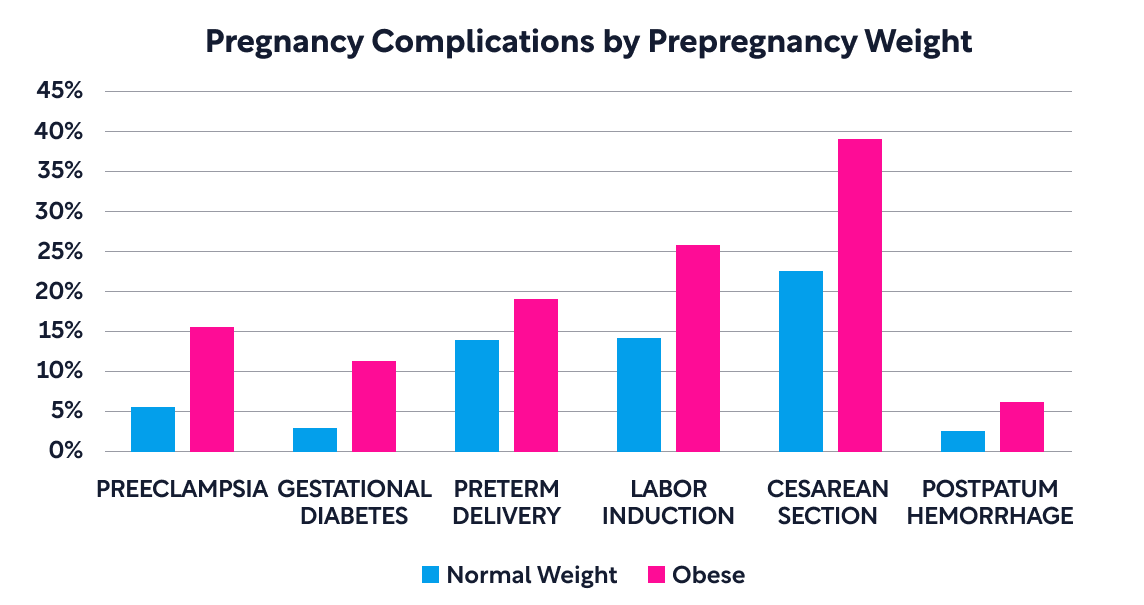

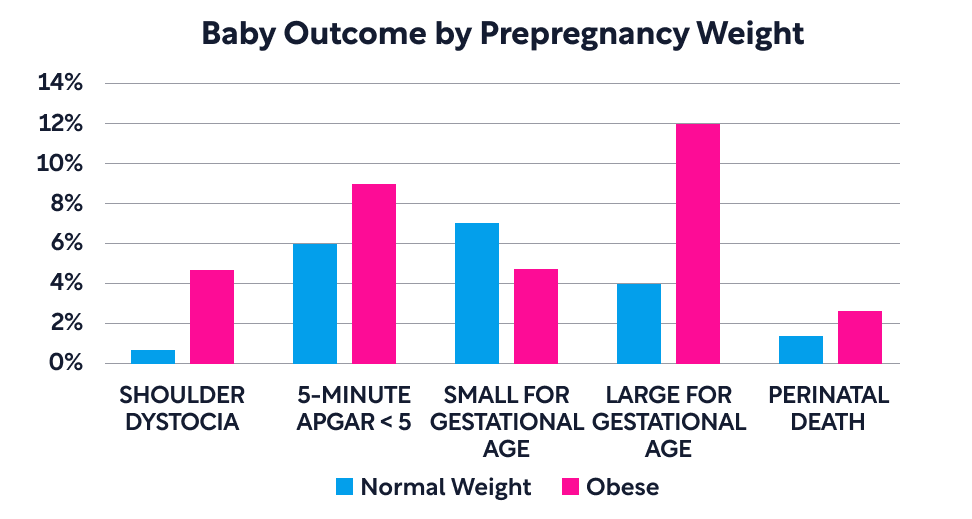

Obese women are less likely to get pregnant and more likely to have pregnancy complications and infant complications. Here are a few graphs illustrating the difference:

(Shoulder dystocia is an emergency occurring during labor in which the baby’s shoulder gets stuck and can’t easily come out behind the pubic bone.)

Overweight women who are neither obese nor of normal weight have risk profiles somewhere in between.

Conception and the Ovulation Cycle

The ovulation cycle lasts 28 days on average. Starting from Day 1, when the period starts, the first 14 days are gearing up for ovulation. On Day 14, the egg is released and travels through the Fallopian tube toward the uterus. This journey takes around 6 days. If the egg is fertilized, it implants in the uterus around Day 23.

Critically, the egg survives only an average of 24 hours, well before it makes it to the uterus. Therefore sperm must be waiting around in the Fallopian tube, right as the egg is released.

Luckily, sperm live up to 5 days in the Fallopian tube. Therefore, the best chance of conception happens the day before or the day of ovulation. Conception can still happen up to 5 days before ovulation, with lower chances.

Here’s a graph of chances of conception depending on day of ovulation cycle, in women aged 26-35:

Myth: It’s best to have sex every other day, so you can hit at least one of the two best days and save up your sperm.

Reality: Chances of conception are nearly identical whether you have sex once, twice, three times, or more in the 6-day window before ovulation. The critical thing is to hit the day of ovulation or the day before.

Fun fact: Out of say ~500 million sperm in an ejaculation, only ~200 will reach the egg and have a chance of fertilization.

Conception and Previous Contraception Use

If you’ve previously used long-term contraception like the pill or IUDs, it may take time to get back on normal ovulation cycles. Your earlier cycles may be longer and may not lead to ovulation. But don’t worry - your previous use of contraception has no long-term effects on fertility.

For women who’ve taken the pill:

- The first month off the pill, 60% have a normal cycle. 9 months after stopping, nearly everyone returns to a normal cycle.

- Women going off the pill were less likely to get pregnant in the first 3 months, but just as likely to get pregnant within a year as women who didn’t take the pill.

- The duration of pill usage has no effect on fertility or time to return to normal cycles.

Women who used IUDs took a month longer to get pregnant than women who stopped using the pill, but otherwise had the same rates of conception.

Detecting Ovulation

There are a few ways of detecting ovulation.

Temperature Charting

Here’s how your body temperature changes in your cycle

- In the first half of your period cycle, your temperature will be low, usually below 98 degrees F.

- The day after ovulation, it’ll increase by 0.5 degree or more.

- If you don’t get pregnant, body temperature will drop the day your period starts; if you do get pregnant, it’ll remain elevated.

To track temperatures accurately, check your temperature when you wake up, before you get out of bed and move around. Travel, jetlag, and fevers can affect this.

Temperature charting accurately identifies the day of ovulation 30% of the time, and 30% of the time it mistakenly points to the day before ovulation. So the odds are decent with this relatively simple method.

The downside to temperature charting is that it only detects after ovulation has occurred - so it’s more useful to track your cycle for conceiving in future cycles, not this one.

Cervical Mucus

Right before you ovulate, your cervical mucus will be stretchy like egg whites (this consistency is better for sperm to swim through). The day when it transitions to this form is a good day to try conceiving.

To study your cervical mucus, reach into your vagina and run your finger around the cervix.

The benefit of tracking cervical mucus is you can detect the day of ovulation in your current cycle, vs temperature charting which detects changes only after. The drawback is that semen can look like mucus, so it’s more accurate a day after sex.

This method has an accuracy rate in about 50%. Some women combine this and temperature charting for a more accurate picture.

Ovulation Detection Sticks

These pee sticks detect luteinizing hormone, which peaks the day before ovulation.

The accuracy of ovulation sticks is strong - it identifies the day of ovulation 100% of the time. Of women randomly given access to ovulation detection sticks, 23% got pregnant within 2 months, vs 15% who didn’t have them.

The downside of ovulation sticks is cost - they run about $30 per month.

Chapter 3: The Two-Week Wait

After you ovulate and try to conceive, it takes about 2 weeks to see if you have your period. What do you do in this time - namely, can you drink alcohol or caffeine, and eat deli meats? (more on these later)

Oster argues that embryos are more resilient than you might think - because the early embryo is a mass of pluripotent cells, any cells that are killed can be replaced by another cell. But there’s a limit - kill too many cells and the embryo will fail to develop.

If you want to stay on the cautionary side, then pretend you’re pregnant in the 2 weeks. Then on the day you find out you’re not pregnant, you can party.

Home pregnancy kits cost ~$5 per test and measure hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin), which is produced by the implanted embryo (to maintain the corpus luteum in the ovaries, which then secretes progesterone). With these kits, the false negative rate is high - only 50% of pregnancies are detected 4 days before a missed period. But the false positive rate is very low - they are very unlikely to tell you you’re pregnant when you’re not.

One downside to early detection is that pregnancy loss is very common - as many as 50% of fertilized eggs don’t result in pregnancy. Normally this ends in what appears to be a heavy period. With early detection kits, you might learn you’re pregnant, only to lose it, which can be very disappointing. Some people may just choose not to detect early and just wait for their period.

Fun fact: hCG used to be detected by injecting urine into infantile mice or rabbits that were then dissected. If the urine contained hCG, the animals would ovulate. Some organizations now collect urine from pregnant women to extract hCG for fertility treatment.

Part 2: First Trimester | Chapter 4: Caffeine, Alcohol, and Tobacco

Congratulations, you’re pregnant! It might have been a journey to get here, but there are still 9 months of things that people worry about.

Pregnancy is usually tracked in terms of weeks (e.g. “I’m 28 weeks in.”) Weeks in pregnancy are counted from the time of your last period. So 5 weeks into pregnancy is 1 week past your missed period.

The first thing we’ll discuss is common vices that people generally advise to stop during pregnancy - caffeine, alcohol, and tobacco.

There’s a lot of stigma and confusion around the use of substances in pregnancy. In perhaps the most provocative part of Expecting Better, Oster argues that caffeine and alcohol, in moderation, show no evidence of being harmful to the child.

To cut to the chase:

- Pregnant women can drink 0.5 drinks a day in the first trimester, and 1 drink a day in the second and third trimesters. This is meant to be a maximum limit per day, not an average. Binge drinking is bad - don’t save up your 7 drinks per week for one night.

- 3-4 cups of coffee per day (about 300-400mg of caffeine) is fine.

- Smoking is never OK.

Poor Studies and Why Myths Exist

Where does all the confusion around caffine and alcohol in studies come from? It starts with academic pregnancy studies that don’t meet a standard of rigor.

To figure out how a behavior like drinking affects child outcomes, pregnancy studies typically 1) study the mother’s behavior and categorize them into groups, 2) follow the children’s outcomes over time, 3) associate the outcomes with the original groups.

But a common problem in pregnancy studies is insufficient controls for confounding factors. In other words, things that can affect child outcomes aren’t tracked, and thus entirely different factors can be affecting child outcomes.

Here’s an example. Picture a study where you divide the population of mothers into abstainers and drinkers, then study their kids. If you picture the type of woman who has 0 drinks a week vs 2 drinks a week vs 10 drinks a week, you can already imagine differences in the child’s environment, such as their education, wealth, and location. When the kids grow up, if you find that children of drinkers end up with behavioral problems, it’s unclear whether it was the drinking or the other factors (like household conditions) that made a difference.

Similarly, people worry that coffee causes miscarriages. But women who drink more coffee tend to be older than those who don’t. What if it’s age that’s causing the miscarriages, and not the caffeine?

In one notable study on alcohol, Oster found a startling difference in cocaine use: 18% of women who didn’t drink reported using cocaine during pregnancy, compared to 45% of those having 1 drink per day!

Not only are the poor studies themselves confusing, their results are then cherry-picked by popular media and distorted into a shocking headline: “1 cup of coffee a day causes miscarriages.” Before you know it, myths start perpetuating.

The gold standard study in medical science is the randomized controlled trial, where people are randomized into a control group and a treatment group. Unfortunately, if there is some risk involved, it’s considered unethical to run a study like this - imagine forcing a group of pregnant women to drink 10 drinks per week!

Another reason cautionary guidelines exist is that doctors fear that allowing some laxity could lead to a slippery slope - if they tell someone that one drink a day is ok, then the patient might creep up to 2-3 drinks per day. Oster finds this understandable, but patronizing.

Alcohol in Pregnancy

The common conception is that no amount of alcohol is safe during pregnancy. Oster argues a more nuanced approach.

The main concern of drinking during pregnancy is fetal alcohol disorder, which manifests in cognitive symptoms like developmental delays and learning difficulties.

Here are some guidelines. Binge drinking (more than 5 drinks at a time) is clearly bad. In one study, binge drinkers in the 2nd/3rd trimester were 15-20 percentage points more likely to have children with language delays than women who don’t drink. This is broadly confirmed by the academic literature.

However, this doesn’t automatically scale linearly. In other words, it doesn’t mean that drinking of any amount is bad. Your body is capable of processing a regular amount of alcohol per hour, and below a certain amount, the fetus may be unaffected. Binge drink, and it overwhelms your body’s systems.

“Drink like a European, not like a frat brother.”

How does alcohol actually affect the fetus? Surprisingly, it’s still unclear. Biologically, the body metabolizes alcohol into acetaldehyde, and then into acetate. Oster argues the acetaldehyde is the toxin that impacts development. It also seems that alcohol itself causes oxidative stress, neuronal structural defects, and alterations in gene expression. Either way, the more alcohol and byproducts you have floating around, the more the fetus is damaged.

Weighing the Evidence on Alcohol

The arguments in favor of light drinking not being a big deal:

- Generally, studies show no impact of drinking up to 1 drink per day on these outcomes: preterm birth, child IQ, test scores, behavior problems.

- In fact, many studies find women who drink moderately have kids with higher IQ scores, but this is likely not causal and may instead correlate with education or social factors.

- Evidence on early drinking and miscarriage risk in first trimester is mixed - some results say no relationship, others show twice the risk drinking >4 drinks/week vs no drinking.

- This study didn’t control for nausea, explained in the caffeine section next.

- Generally, Europe is more permissive about light drinking during pregnancy, yet there’s no evidence of greater rates of fetal alcohol syndrome or in population differences in IQ.

(Shorform caveats:

- It’s not clear how mothers with alcohol enzyme deficiencies (aka ‘Asian glow’) may react differently, given that acetaldehyde levels remain elevated at a 5-10x level.

- Not all drinking women lead to kids with fetal alcohol syndrome, much like how ‘only’ 15% of smokers will develop lung cancer. The CDC’s estimate is 2-5% of all children may have fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

- One dissenter, Susan Astley (also an academic) argues that Oster’s studies look at children too early (age 5 and below) but that most cognitive deficits appear at age 10 and later. Furthermore, IQ may appear normal, but language and memory deficits weren’t measured as part of the studies.

- She also argues that 1 of 14 children with fetal alcohol syndrome had a reported exposure of just 1 drink per day, so mild drinking can still lead to FAS. This isn’t as convincing, though, as Oster would argue that the risk of 1 drink per day leading to FAS is quite low.)

Caffeine

The concern with caffeine is that it can increase risk of miscarriage and limit blood flow to the placenta.

The evidence is mixed - some studies find a 25% miscarriage rate for >200mg caffeine a day (about 1-2 cups of coffee), and 13% miscarriage rate for less caffeine consumption. High rates of caffeine (>5 cups of coffee a day) more consistently led to 50-100% increase in risk of miscarriage.

Other studies find no relationship in miscarriage or baby health. Tea and cola are less consistently linked with miscarriage than coffee, which is odd since they all contain caffeine as the active ingredient. Furthermore, decaf coffee may be as strongly linked to miscarriage as regular coffee.

Oster argues that caffeine pregnancy studies have a big confound with nausea. Nausea is apparently a good sign about the health of pregnancy and indicates a lower risk of miscarriage. However, you’re less likely to drink coffee when nauseated. So women who drink caffeine may simply be less nauseous and become more likely to have miscarriages.

Oster believes it’s completely safe to have up to 2 cups of coffee a day, and probably OK to have 3-4 cups. Beyond that, the evidence is mixed and may be confounded with nausea.

Tobacco

This one’s pretty simple: tobacco is not recommended at any time in pregnancy or in life. The mechanism of how tobacco causes harm is believed to be nicotine and carbon monoxide restricting oxygen to the fetus and constricting blood vessels in the placenta.

Smoking increases the risk of a lot of complications: anemia, placental abruption, small baby, stillbirths, and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Smoking may cause 5x the risk of SIDS; 86% of SIDS deaths in England were with mothers who smoked.

And unlike alcohol, where moderate drinking didn’t show severe effects, moderate smoking (1-8 cigarettes a day) showed similar risks to more than a pack a day.

Luckily, quitting smoking in the middle of pregnancy decreases complications. Nicotine replacement therapies show some evidence of being helpful, but the problem is these therapies aren’t that successful in stopping women from smoking.

Chapter 5: Miscarriages

A minority of pregnancies end in miscarriage, and there’s largely nothing you can do about it. 90% of miscarriages in the first trimester are due to chromosomal problems at conception.

Here’s the risk of miscarriage by week:

| Week | Chance of miscarriage |

| 6th week | 11% |

| 7th week | 7.2% |

| 8th week | 5.8% |

| 9th week | 3.3% |

| 10th week | 3.2% |

| 11th week | 1.9% |

The 6th week is the second week after your missed period, and often the time of the first prenatal visit when you get an ultrasound. It has the highest risk of miscarriage, between 10-15%. After week 12, the risk is 1-2%.

It’s common to announce after the first trimester (roughly 12 weeks), but the risk of miscarriage decreases substantially by week 9.

Other factors affecting miscarriage:

- Women with a previous miscarriage have a miscarriage chance of 25% in first trimester, compared to 4-5% for first pregnancies or women with a previous successful pregnancy.

- Age increases miscarriage rate: women below age 20 have a miscarriage rate of 4.4%; women aged 20-35 have a miscarriage rate of 6.7%; and women over 35 have a 19% miscarriage rate.

- IVF pregnancies have miscarriage rates of 30%, vs 19% for natural pregnancies.

- Vaginal bleeding signals increased risk - 13% of women with bleeding have miscarriages, vs 4.2% without.

- Lack of nausea signals a higher miscarriage rate.

- Low levels of progesterone may contribute to miscarriage.

Chapter 6: Foods to Avoid and Not

Pregnant women are commonly recommended to avoid a long list of foods - raw eggs, raw fish, cheeses, deli meats, to name a few. The general fear is that food illnesses can bear a risk to the fetus.

Oster argues that many food illnesses are actually no riskier than when you’re not pregnant. But two forms are, and are worth avoiding.

Foods Commonly Avoided that are Fine

Typical food poisoning is caused by Salmonella, E.coli, and Campylobacter. These pathogens cause diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting, but do not usually affect the fetus.

For foods more at risk of harboring these bacteria, like raw eggs, raw fish, and shellfish, use your standard caution. Chances are you haven’t gotten food poisoning more than once a year, and this isn’t going to get more likely when you’re pregnant.

Foods to Avoid

Oster acknowledges two illnesses that are harmful:

Toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasmosis affects 1 in 1,500 babies and causes mental retardation, blindness, and epilepsy. Acute toxoplasmosis in the mother has a 30% chance of infecting the baby.

You can get toxoplasmosis from undercooked meats, dried/cured meat, and unwashed vegetables and fruits. Cat litter is actually less likely than the above dietary sources.

If you already have toxoplasmosis (25% in the US do), then there’s no risk to your baby.

Listeria

Listeria affects 1 in 8,000 babies and, in 10-50% of pregnant women who are infected, can cause miscarriage, preterm birth, stillbirth, meningitis, and neurological problems. The mechanism seems to be infection of the placenta, which triggers defense by the mother and expelling the placenta.

The sources for listeria outbreaks are sporadic and unclear, with sources in ice cream, cantaloupes, celery, and deli meats. Oster noticed a pattern in queso fresco (Mexican soft cheese) and deli turkey meat and chose to ignore those.

Listeria grows well at fridge temperatures, so if you want to be safer, chuck out anything that’s been in the fridge for too long

The Best Fish to Eat

Fish have two competing effects on the fetus:

- High mercury lowers IQ.

- A 1 ug/g increase in mercury sampling causes a decrease of 0.7 IQ points. In other words, the average American woman and the highest mercury-exposed woman produces a 3.5 IQ point difference in kids.

- Predator fish and long-living fish (listed below) have the highest levels of mercury. The former eats other fish harboring mercury, and the latter accumulates mercury over a long lifetime.

- Omega-3 fatty acids increase IQ.

- Increasing DHA fatty acids by 1 g/day would increase IQ by 1.3 points.

The solution is to eat high omega-3 fish with low mercury. The best fish to eat are: salmon, herring, sardines, pollock, and mackerel.

The worst fish that you should AVOID are: orange roughy, canned tuna, king mackerel, grouper, shark, and swordfish. These contain low omega-3 but have high mercury.

These fish are somewhere in the middle: tilefish, halibut, sushi-grade tuna, flounder, and snapper.

Chapter 7: Nausea

Nausea is very common in pregnancy - 90% of women report nausea, and >50% report vomiting. The important thing concerning nausea is to know when you have an unusually high level of nausea, and when to seek help.

Here’s what normal nausea looks like:

- Nausea peaks at 5-8 weeks pregnant, with about 45% of women reporting vomiting; it declines steadily from then on. In weeks 13-16, about 25% report vomiting. By week 20, only about 8% of women continue vomiting.

- Normal levels of vomiting aren’t as bad as you might expect - it’s concentrated in an average of 6 days over the whole pregnancy, occurs fewer than 3 times a day, and should not lead to dehydration or weight loss.

In other words, if you are vomiting everyday for weeks, this is atypical.

Luckily, nausea is inversely correlated with miscarriages - in one study, 30% of women without nausea had a miscarriage, compared to 8% who did.

Pregnant women have had scares with anti-nausea medication before - thalidomide caused birth defects, and Bendectin (B6 + Unisom) was pulled off the market. However, Oster argues that the mother’s comfort is quite important, particularly if it affects her diet and well-being, and OTC anti-nausea medications are not shown to be bad.

Oster’s recommendations for nausea cures, in declining order of preference:

- Eat smaller meals

- Vitamin B6

- Vitamin B6 + Unisom

- Zofran

Chapter 8: Prenatal Screening and Testing

The primary purpose of prenatal screening is to detect chromosomal abnormalities, the most common being Down Syndrome, or trisomy 21. Tests also screen for the rarer Edwards syndrome (trisomy 18) and Patau syndrome (trisomy 13), both more severe than Down Syndrome with babies rarely surviving their first year. Families at high risk for genetic disorders may also screen.

The risk of Down Syndrome increases with maternal age, from 1 in 1488 from ages 20-24, to 1 in 746 in ages 30-34, to 1 in 30 for age 45 (a fuller chart is shown later). For some comparison, the risk of a car accident in the next year is 1 in 50, and the risk of being audited in the next year is 1 in 200.

There are largely two types of screening: non-invasive (cell-free fetal DNA, ultrasound), and invasive (amniocentesis, chorionic villus sampling). Non-invasive tests pose no risk to the fetus but are more prone to false positives and false negatives. In contrast, invasive tests have higher accuracy, but pose a risk of miscarriage (according to Oster, 1 in 800).

Spoiling the punchline: cell-free fetal DNA tests have advanced non-invasive screening considerably from the ultrasound days.

Plan Ahead Before Screening

Typically, people consider getting a non-invasive screen first, then depending on the results, they might get an invasive screen.

Before getting a screen, it’s useful to consider what you’re going to do based on the news you receive. For some parents, screening may have no point - no matter what they find, they’ll continue with the pregnancy. Then testing would just cause undue anxiety and may be unnecessary.

If you do want a test, then consider what you’ll do if you get a positive or negative result. For instance, if you get a non-invasive test and it comes back negative (things check out as normal), would you get an invasive test anyway to be sure? If so, then you might just skip to the invasive test anyway.

Noninvasive Test: Cell-free Fetal DNA

Cell-free fetal DNA tests use fetal DNA that is circulating in the mother’s bloodstream.

The mother’s bloodstream contains not just fetal cells but also fetal DNA outside of cells. In fact, 10-20% of DNA isolated from maternal plasma is from the fetus.

Theoretically, if the fetal DNA could be isolated fully from the mother’s DNA, then full genomic sequencing could occur. We’re not quite there yet, but bulk defects can still be detected - for instance, if a higher than expected proportion of chromosome 21 is in the mix, there’s a good chance it indicates trisomy 21.

The sensitivity (true positive rate, or accurate detection of a disorder) is remarkably high - in one large-scale study, 99.1% of trisomies are detected with this procedure. The false negative rate is also low, at 0.05% (of 146,000 women without Down Syndrome, 61 were given a false positive).

Given your age and test result, then, what is the likelihood of your child having Down Syndrome? Here’s a helpful chart:

| Age | Risk of Down Syndrome | With negative test result, chance of Down Syndrome | With positive test result, chance of Down Syndrome |

| 20-24 | 1 in 1488 | 1 in 179,830 | 1 in 1.8 (55.6%) |

| 25-29 | 1 in 1118 | 1 in 135,085 | 1 in 1.6 (62.5%) |

| 30-34 | 1 in 746 | 1 in 90,097 | 1 in 1.4 (71.4%) |

| 35 | 1 in 374 | 1 in 45,109 | 1 in 1.2 (83.3%) |

| 36 | 1in 289 | 1 in 34,830 | 1 in 1.15 (87.0%) |

| 37 | 1 in 224 | 1 in 26,969 | 1 in 1.12 |

| 38 | 1 in 173 | 1 in 20,801 | 1 in 1.09 |

| 39 | 1 in 136 | 1 in 16,327 | 1 in 1.07 (93.5%) |

| 40 | 1 in 106 | 1 in 12,699 | 1 in 1.06 |

| 41 | 1 in 82 | 1 in 9,796 | 1 in 1.04 |

| 42 | 1 in 63 | 1 in 7,498 | 1 in 1.03 (97.1%) |

| 43 | 1 in 49 | 1 in 5,805 | 1 in 1.03 |

| 44 | 1 in 38 | 1 in 4,475 | 1 in 1.02 |

| 45 | 1 in 30 | 1 in 3,508 | 1 in 1.01 (99.0%) |

In essence, if you get a positive result, it’s very likely the child has Down Syndrome; and if it’s negative, it’s very unlikely the test is wrong.

If you get a positive result when you’re younger, the chances that the child actually has Down Syndrome are lower as well.

(Shortform note: the true positive rate increases with age because the risk increases a lot with age. When the baseline rate is high and the test is positive, chances are better that the test is correct, compared to younger mothers.)

Noninvasive Test: Ultrasound + Blood Test

The newer cell-free fetal DNA test may not be covered by insurance until you’re over 35. The traditional screen consists of an ultrasound to detect nuchal translucency (fluid behind the baby’s neck) and a blood test for hormones in maternal blood (PAPP-A, hCG).

This test’s accuracy is much worse than the cell-free DNA test - it detects only 90% of Down Syndrome cases (vs 99%), and it has a false positive rate of 6.3% (vs 0.05%).

An additional second trimester test draws blood and tests for alpha-fetoprotein, hCG, unconjugated estriol, and inhibin A. Combined altogether, the performance improves - up to 97% of Down Syndrome cases are successfully detected.

(Shortform note: the author doesn’t comment on the accuracy of combining the cell-free fetal DNA with the noninvasive test, but given the accuracy of the cell-free test, things may not improve by much.)

Invasive Test: CVS and Amniocentesis

Both invasive tests use a needle to extract something from the womb - in chorionic villi sampling (CVS) it’s part of the placenta; in amniocentesis, it’s amniotic fluid. CVS is performed earlier between 10-12 weeks, while amniocentesis is done between 16-20 weeks.

The accuracy of both tests is very high (Shortform note: the author doesn’t put numbers to this).

The risk of miscarriage is the worrisome part - inserting the needle might hit the fetus or pierce the placenta. Common wisdom puts the risk of miscarriage at 1 in 200.

Oster argues this number is outdated and based on research from the 1970s, which found a non-significant increase of miscarriages from 3.2% to 3.5%. With better procedures (using ultrasound to guide the needle), Oster believes the risk of miscarriage is now closer to 1 in 800, if there is any risk at all.

However, one factor may increase risk - the popularity of cell-free DNA testing has lowered the need for CVS, and practitioners may become rusty. So if you want to get invasive testing, go to someone who still does them often.

Making a Choice

Now equipped with this information, you can make a choice about risks and what you gain.

For instance, if you’re 35, get a cell-free DNA test, and receive a negative result, the baby’s risk of Down Syndrome is 1 in 45,109. The invasive test has a chance of miscarriage of 1 in 800. Do you think that the risk of unexpectedly having a Down Syndrome child is 56 times worse (45109 / 800) than having a miscarriage? If yes, then proceed to the invasive test.

For what it’s worth, Oster chose ultrasound screening for her first child at age 31. For her second child at age 35, she believed the risk of miscarriage was less important now that they already had one child, and she chose to have amniocentesis in the second trimester. As Oster stresses, this was her personal choice, not what she dictates for everyone.

Chapter 9: Forbidden Activities

Just as common as prescriptions on diet during pregnancy are prescriptions on activities like gardening and hot tubs. Here’s a run-down of common activities commonly barred during pregnancy.

Cat Litter and Gardening

Cats present a risk for toxoplasmosis only during the cat’s first exposure. Therefore, older cats that have already had it, cats that don’t eat raw meat, and cats that don’t hunt outside are less likely to have toxoplasmosis. If the cat has kittens when you’re pregnant, risk increases.

There is a strong association between working with soil and toxoplasmosis. So if you garden, wear gloves and maybe a mask.

Hair Dye

The misconception around hair dye causing birth defects likely began with experiments that dosed animals at unnaturally high amounts. In humans, a study of hairdressers found a small but significant increase in low-birth-weight babies, but this was not replicated and may be due to other things (like standing a lot).

Hair dye is likely safe, particularly after the first trimester.

High Temperatures - Hot Tubs, Baths, Hot Yoga

Raising your body temperature above 101 degrees in the first trimester increases risk of gastroschisis and anencephaly, a neural tube defect.

Hot tubs and Bikram Yoga are around 105 degrees, as are very hot days, so avoid these in the first trimester. After the neural tube forms in first trimester, it may be safer.

A Spanish study did find that very hot days seemed to induce labor earlier (by about 5 days). So if you’re near your due date, consider staying inside on hot days.

Sex

The baby is protected in a giant cushiony fluid sac, and sex isn’t going to hurt it. Go nuts.

The cervix is more sensitive during pregnancy, so hitting it may induce some bleeding, which is normal.

Radiation and Airplanes

The recommended limit on radiation exposure for the duration of pregnancy is 1 mSv (millisievert). This is conservative, with experts suggesting there are no definitive data showing fetal harm at doses below 20 mSv. Oster does note that exposure to twice this limit might increase the risk of the child having a fatal cancer by 1 in 5,000.

How does this translate to flying? A single 4-hour flight would deliver at most 0.02 mSv, or 2% of the limit. And flight attendants receive around 1.5 mSv per year, so each individual flight is not a big deal.

How about airport security? A single screening has a maximum of 0.25 μSv, or 0.025% of the limit. In other words, you could get a screening every single day and that would represent 9% of your annual conservative limit.

In other words, unless you’re a flight attendant, you probably won’t reach the conservative limit. But you can always opt for the pat-down instead of the X-ray.

(Shortform note: to put these radiation doses into perspective, here are examples of radiation doses in normal life:

- 0.25μSv: maximum limit on dose from a single airport security screening

- 5-10μSv: one set of dental X-rays

- 0.3-0.5mSv: dosage per 100 flight hours for air crews

- 0.5mSv: one two-view mammogram

- 1mSv: the dose limit for typical members of the public per year

- 1.5 mSv: flight attendants receive this amount per year

- 10-30 mSv: a single full-body CT scan

- 4-5 Sv: dose, if administered in short duration, that would kill a human with 50% risk in 30 days

- 64 Sv: nonfatal dose given to Albert Stevens over 20 years in a 1945 plutonium injection experiment)

Part 3: The Second Trimester | Chapter 10: Eating and Weight Gain

Weight gain is a top topic for your prenatal care visits. Gain too much or too little weight, and the child is at risk (and your doctor will probably complain). Even more, the concept of “eating for two” may stimulate pregnant women to overeat.

Here are the guidelines for suggested weight gain over pregnancy:

| Starting weight | Suggested weight gain (lb) | Weight gain per week (lb) |

| Underweight (BMI < 18.5) | 28-40 | 0.85 |

| Normal Weight (BMI 18.5-25) | 25-35 | 0.75 |

| Overweight (BMI 25-30) | 15-25 | 0.50 |

| Obese (BMI > 30) | 11-20 | 0.38 |

Too little or too much weight gain (less than 22 pounds and more than 45 pounds, respectively, for a woman starting at normal weight), increases risk of preterm birth by around 1.4x. But both have unique issues.

Risks of Too Little Weight Gain

Eating too little in pregnancy could cause the fetus to be smaller for gestational age (SGA). Specifically:

- Gaining 10 pounds lower than the recommendation doubles risk of SGA babies (from 10% to 20%) and halves risk of too-large babies (from 5% to 2.5%).

- 42% of SGA babies have complications of difficulty breathing, irregular blood sugar regulation, and abnormal neurological signs

- A SGA baby born prematurely has higher risk of complications than an appropriate weight baby. In one study:

- Chronic lung disease increased from 29% to 57%

- Mortality increased from 17% to 33%

Risks of Too Much Weight Gain

Eating too much in pregnancy could cause the fetus to be large for gestational age (LGA):

- Gaining 10 lb more than recommendation doubles risk of LGA babies (from 5% to 10%) and halves risk of SGA babies (from 10% to 5%)

- LGA babies roughly double the risk of requiring C-section and instrument-assisted delivery, and roughly triple risk of needing resuscitation or ICU transfer. (Shortform note: we could not find the baseline rates from Oster’s references.)

Another concern is that too much weight gain may cause your child to be overweight later in life. This has been shown in animal studies, with a possible mechanism being insulin resistance in the womb leading to insulin resistance in life.

But this is hard to control from environmental factors and parent habits, and Oster argues the effects are small. One long-term study found that for every kg Mom gained, BMI increased by 0.03. In other words, gaining 10 pounds over the recommendation would increase the child’s future BMI by 0.13 - in the range of 1-2 pounds.

In general, the risks of too little weight gain are more severe than those of too much weight gain.

Returning to Normal Weight after Pregnancy

Some women may undereat in the hopes that they won’t have to take off weight after pregnancy.

One study found that women who gained the recommended amount ended up 5 lbs heavier 6 months after delivery. But 90% of women starting out at normal weight had returned to normal weight by 24 months postpartum.

Given that the risks of SGA babies are far worse, Oster argues that it’s far better to err on gaining too much weight than too little. And gaining 1 pound over the guideline (36 instead of 35 pounds) is not a big deal. While doctors currently get equally concerned over both too little and too much weight gain, Oster argues doctors should weigh too little weight gain much more strongly.

Chapter 11: The Baby’s Gender

About half of couples choose to learn about their baby’s gender before birth.

You can find your baby’s gender through a maternal blood test (soon after pregnancy), CVS test (first trimester), or in ultrasound (typically around 20 weeks).

If you don’t want to put your baby's gender to chance, you can dictate your baby’s gender through sperm sorting, then artificial insemination/IVF.

(Shortform note: fun fact - sperm sorting is done through FACS, or fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Also, “family balancing” is the polite term for gender selection.)

Things that don’t work to discover or influence the baby’s gender:

- Timing conception does not influence baby gender.

- Some believe that Y sperm (leading to males) are fast swimmers but die off quickly, so if you want to have a girl, then have sex earlier. This is called the Shettles method. There is no evidence that this works.

- Some believe female fetuses have faster heart rates. This is a myth: fetal heart rate does not differ between genders.

Chapter 12: Exercising while Pregnant

There is little evidence suggesting that exercise has any effects on preterm birth, rate of C-section, length of labor, or baby APGAR scores. Exercise does show a modestly lower weight gain (1.3 fewer pounds).

Exercises to consider:

- Kegels

- These exercise your pelvic floor muscles

- 3 sets of 8 kegels per day improves urinary continence during late pregnancy and postpartum

- A small study showed women in Kegels experimental group showed shorter time pushing (40 vs 45 minutes)

- Prenatal Yoga

- Small studies suggest yoga reduces discomfort in late pregnancy, decreased length of labor (2.5 hours shorter), and lower levels of pain during labor

Exercises to avoid:

- Exercise with risk of physical trauma or falling (skiing, football, climbing) can cause the placenta to detach

- Very high heart rate exercise (eg 90% of max) can decrease blood flow to baby

- Doctors suggest avoiding sit-ups or crunches where you lie flat on your back, since this may drop blood pressure and reduce blood flow.

- Oster suggests this is actually fine; if you feel uncomfortable while doing it, then just stop.

Insomnia

Sleeping may be tough in later pregnancy due to aches and positioning issues.

The recommendation is to sleep on the left side, not the back. The evidence is currently inconclusive - some studies show sleeping on the back or right side doubled stillbirth rate. However, a blood flow study found that lying on your back found no particularly bad impact on blood flow.

Some women feel faint on their backs - if so, then they should switch to their left side. If you don’t feel faint, it’s probably fine, though if you can sleep on your left, that’s preferred.

Taking OTC sleep aids like Unisom are fine. Ambien has mixed safety data, but Oster believes it’s fine occasionally.

Chapter 13: Pharmaceuticals while Pregnant

The baby is exposed to most drugs the mother takes, except for large molecules (e.g. heparin) and drugs that get stuck in the placenta (e.g. buprenorphine).

Drug safety is hard to test in pregnant mothers because of ethical concerns - if there is risk of damage, then exposing a fraction of mothers to a drug seems unspeakable. Furthermore, medicine has a traumatic memory from the use of anti-nausea drug thalidomide in the 1950s, leading to thousands of infants with birth defects and thousands of deaths.

Therefore, many drugs that are probably safe for pregnant women don’t get an explicit clearance from the FDA.

The FDA classifies drugs into five categories (A B C D X), based on strength of evidence on safety:

Category A

- Definition: Well-controlled human studies show no risk to fetus in any trimester.

- Examples

- Folic acid

- Levothyroxine (hypothyroidism)

Category B

- Definition: No well-controlled human studies and animal studies have shown risk to a fetus, OR animal studies show risk but well-controlled human studies show no risk.

- Includes common substances that are unethical to experiment with by withholding from a control group, like vitamins.

- Examples:

- Macrobid/nitrofurantoin (antibiotic)

- Amoxicillin (antibiotic)

- Metformin (diabetes)

- Tylenol/acetaminophen

- Claritin

- Benadryl

- Pepcid AC (heartburn)

Category C

- Definition: No well-controlled human studies. Either animal studies have shown problems for the fetus, OR there have been no animal studies.

- The broadest category - includes both drugs that show no problems in small animal and human studies, and drugs that show damage in animal studies.

- Examples:

- Ciprofloxacin (antibiotic)

- Gabapentin (epilepsy, nerve pain)

- Vicodin/hydrocodone (pain)

- Ambien (insomnia)

- Prilosec (heartburn)

- Ibuprofen (pain)

Category D

- Definition: Evidence of harm to fetus in human studies, but benefits may outweigh risks in certain situations.

- Once a drug falls in this bucket, it’s hard to get out given how difficult it is to prescribe and get new studies.

- Examples:

- Paxil/paroxetine (depression)

- Lorazepam (anxiety)

- Prinivil/lisinopril (hypertension)

- Tetracycline (antibiotic, acne)

- Aspirin

Category X

- Definition: Should not be taken during pregnancy under any circumstances.

- Also includes drugs that have no purpose during pregnancy, like oral contraceptives

- Examples:

- Accutane/isotretinoin (acne)

- Leflunomide (arthritis)

- Warfarin (anticoagulant)

- Lipitor/atorvastatin, Zocor/simvastatin (high cholesterol)

- Finasteride (enlarged prostate)

Part 4: The Third Trimester | Chapter 14: Premature Birth

A premature birth occurs before 36 weeks and occurs in 12% of pregnancies. Early-term is between 37-38 weeks, and full-term is 39 and beyond.

Over the past decades, survival for preterm babies has increased dramatically due to improvements like assisted ventilation (lungs develop later in pregnancy). It’s a marvel that even babies born at 22 weeks still have a shot at survival.

However, premature children are more likely to get sick, have lower IQs, and may have vision/hearing problems. 75% of 5-year-olds born before 30 weeks have a disability (vs 27% of full-term births). Their IQs were 5-14 points lower.

Here’s a table of % of births occurring at each week of gestation:

| Weeks of Gestation | % of Births | Probability of Death in First Year |

| 22 | 0.05% | 77.1% |

| 23 | 0.06% | 62.6% |

| 24 | 0.09% | 39.3% |

| 25 | 0.10% | 26.0% |

| 26 | 0.11% | 18.1% |

| 27 | 0.12% | 13.6% |

| 28 | 0.17% | 7.5% |

| 29 | 0.20% | 5.5% |

| 30 | 0.28% | 4.0% |

| 31 | 0.36% | 3.2% |

| 32 | 0.51% | 2.1% |

| 33 | 0.78% | 1.5% |

| 34 | 1.39% | 1.1% |

| 35 | 2.33% | 0.8% |

| 36 | 4.37% | 0.6% |

| 37+ | 89.09% | 0.2% |

Chances of a preterm baby are thus sizable, but still in the small minority.

Delaying Labor

If you go into labor early, what happens?

- You receive tocolytics (eg magnesium sulfate) to suppress contractions and delay birth for 1-2 days.

- You receive steroid shots, which speeds up fetal development.

- Steroids result in 30% decrease in fetal death.

- You can get transported to a hospital with a higher-level NICU, with more sophisticated equipment to handle very preterm infants.

Oster argues there is no evidence that bedrest works at preventing preterm birth. It also entails risk from taking leave from work and medical risks like muscle atrophy and weight loss.

Chapter 15: High-Risk Pregnancy

This scary chapter goes through major complications of pregnancy in the third trimester, their consequences, and treatments.

(Shortform note: Oster did not include the baseline rates for these and risk factors, so we did the research and added them here (thus, any inaccuracies are not the book’s fault). Mercifully, the risk for any grave condition is usually <1%.)

Generally, if a particular complication happens in your first pregnancy, it’s likely to happen in future pregnancies.

Placenta Previa

What: Placenta covers the cervix, partially or fully.

Rate: 0.5%

Risk Factors

- Maternal age > 40 and < 20

- Prior C-section

- Prior abortion

Consequences

- Vaginal bleeding with potential for hemorrhage

- Preterm birth

Management

- Most self-resolve

- If continues to term, C-section around 36 weeks

(Note the vicious cycle here - placenta previa leads to C-sections, which increases risk of placenta previa.)

Placental Abruption

What: Placenta detaches from the uterine wall

Rate: 0.5%

Risk Factors

- Maternal trauma

- Pre-eclampsia

- Chronic hypertension

- Maternal age > 40 and < 20

Consequences

- Painful contractions and vaginal bleeding

- Preterm birth

- Fetal growth restriction

- Need for C-section

Management

- If full-term, deliver baby

- If preterm, depends on severity of abruption

Gestational Diabetes

What: Diabetes diagnosed during pregnancy

Rate: 3-9%

Risk Factors

- Obesity and overweight

- Family history of type 2 diabetes

- Maternal age > 35

Consequences

- Higher risk of macrosomia (large for gestational age, > 8lb 13oz at birth)

- Delivery may need instruments or C-section

- Risk for stillbirth, neonatal metabolic problems

Management

- Glucose monitoring and control

Rh Alloimmunization

What: Baby has Rh+ blood, Mom has Rh-. Mother produces antibodies that can cross placenta and lead to destruction of fetal red blood cells.

Rate: 0.1%

Risk Factors

- Requirement: mother must be Rh- and father is Rh+ (homozygous or heterozygous)

- Amniocentesis/CVS causes blood mixing

- Bleeding in pregnancy

- Previous pregnancies with Rh incompatibility (first baby is less at risk)

Consequences

- Risk of fetal anemia and hyperbilirubinemia

Management

- Rhogam shot at 28 weeks and after delivery. This destroys fetal red blood cells before the mother can develop immunity to them. This dramatically reduces risk of Rh disease.

Cervical Insufficiency/Incompetence

What: Painless dilation of the cervix before reaching term

Rate: 1-2%

Risk Factors

- History of cervical biopsy

- Repeated procedures to cervix during pregnancy

- Significant trauma to cervix

Consequences

- 2nd trimester miscarriage

- Very preterm birth

Management

- Cervical length screening

- Progesterone treatment

- Cerclage (sutures above cervix opening) at weeks 14-16

Fetal Growth Restriction

What: Poor fetal growth, usually due to poor nutrition or inadequate oxygen to fetus

Rate: 3-10%

Risk Factors

- Poor weight gain

- Poor nutrition

- Smoking

- Alcohol

- Diabetes

- Hypertension, cardiovascular disease

Consequences

- Low birth weight

- Preterm birth

- Still birth

- Metabolic, breathing problems

Management

- Continual evaluation of growth

- May induce early delivery if baby would be better off outside mother

Preeclampsia, Eclampsia, HELLP Syndrome

What: High blood pressure (>140/90) with increased protein in urine. Symptoms include headache, abdominal pain, sudden weight gain.

- Eclampsia involves seizures resulting from multi-organ failure, vascular permeability, and cerebral edema.

- HELLP = hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets.

- Possible mechanism involves abnormal vascularization of placenta, causing hypoxia and release of factors causing inflammation.

Rate: 3-5%

Risk Factors

- Obesity

- Hypertension

- Older age

- Diabetes

- Mother >35 years

Consequences

- Multi-organ failure

- Maternal and fetal death

Management

- Blood pressure management

- Aspirin

- Delivery of baby

Placenta Accreta

What: Placenta forms an abnormally firm and deep attachment to the uterine wall.

Rate: 0.3%

Risk Factors

Consequences

- Hemorrhage at time of delivery

- Damage to local organs

- Maternal death

Management

- C-section followed by hysterectomy

Chapter 16: Inducing Labor at Late Pregnancy

As you cross the 36th week of pregnancy, you’re past the preterm period (hooray!) but then you start worrying the baby will never come out.

18% of babies are born week 38, 30% on week 39, and 17% on week 40. In sum, 70% of babies are born before their due date.

Here’s the chance of pregnancy for every week you reach:

| Week of pregnancy | Chance of birth this week if still pregnant this week |

| 35 | 3% |

| 36 | 5% |

| 37 | 11% |

| 38 | 25% |

| 39 | 46% |

| 40 | 59% |

| 41 | 58% |

| 42 | 100% (induced) |

Starting at week 37, your doctor will measure your cervix for a few predictors of labor:

- Cervical thinness (effacement)

- Women who were >60% effaced at 37 weeks were 98% likely to go into labor before due date. <40% effaced meant almost none went into labor before due date.

- Cervical dilation

- Baby drops down in pelvis a few days/weeks prior to labor

- Bishop score - combines the above into a score from 0 to 13. > 6 is fairly advanced

Bishop score and cervical effacement are predictive of vaginal deliveries.

At 42 weeks, you’re almost certain to have labor induced, likely with Pitocin (synthetic oxytocin), which stimulates contractions. This is to reduce the risk of stillbirth with babies who are born too late. Oster argues that Pitocin may increase pain in labor and increase risk of C-section, which is why she was willing to wait until the very last moment to induce.

Part 5: Labor and Delivery | Chapter 18-19: Giving Labor

Here’s a timeline of labor:

First Stage: Dilation (few hours to a few days)

- Early Labor: 1-3 cm (least pain)

- Mild and infrequent contractions

- Sometimes not even noticeable over weeks(!)

- Active Labor: 3-7 cm (more intense)

- Transition: 7-10 cm (horrible, but quicker)

- Contractions can come every 2 minutes and last 90 seconds

Second Stage: Pushing (few minutes to a few hours)

Third Stage: Placenta (short)

Generally, labor progresses at an average of 1 cm of dilation per hour, but this rate can be slower in early labor (2 hours without any change in dilation) and speeds up near the end (going from 7 to 10 cm in < 90 minutes).

If the cervix doesn’t open quickly enough, you can be given Pitocin to induce contractions or a C-section if the baby’s heart rate is dropping.

C-sections happen in 30% of births in the US, but they are not the preferred mode of delivery since they entail slower recovery. Once you have a C-section, you’ll be recommended to have C-sections for future babies. Vaginal births after C-section may increase infant complications and maternal hemorrhage.

Baby Position

Babies are normally delivered head-first. Coming feet-first is called breech, and it carries risk of oxygen deprivation to the baby or injury to the skull. Thus, most breech babies are delivered via C-section.

The direction a baby is facing can change throughout pregnancy - at 28 weeks, 25% of babies are in breech; by delivery, it’s only 3-4%.

The baby’s position can also be manipulated in the womb through external cephalic version, where the baby is manually turned to normal position. This is usually done after 37 weeks, since before then most breech positions resolve naturally.

Should You Epidural?

An epidural is an analgesic injected into the spine during the first stage of labor. It drastically reduces the pain of labor to virtually no pain, and it helps the mother get rest for the physically demanding pushing part of labor.

Epidurals are very popular and are used in about 66% of births in the US.

For the baby, epidurals don’t have big differences in APGAR score, fetal distress, or NICU time. The epidural does raise the risk of a maternal fever during labor, which could prompt doctors to administer antibiotics to be safe and thus expose the baby to antibiotics.

Cons of an epidural:

- Increased risk of forceps or vacuum extractor in delivery

- Greater use of C-section for fetal distress

- Longer pushing time (15 minutes)

- Greater use of Pitocin in labor to compensate for slowing in contractions

- Higher chance of baby facing up at birth (possibly due to less walking)

- Greater chance of maternal hypotension

- Longer recovery postpartum

- Increased chance of fever in labor

- 1/200 epidurals cause a wet tap, where the needle goes into the spinal fluid and causes a headache for a few days

Oster ultimately chose to deliver both children without an epidural.

Chapter 20: The Birth Plan

Birth plans are short documents that describe what you want to happen during your birth and what treatments you’re willing to accept in which situations. OBs and nurses have a slight aversion to them because they may signal some inflexibility to do what they think is best in critical situations.

But Oster argues it’s far better to think about hard decisions and articulate your preferences beforehand than to come up with them on the fly.

Here are the elements of her birth plan:

- Avoid inducing labor. If water breaks before contractions start, wait 12 hours and induce labor only if labor has not started by then. In this scenario, avoid digital vaginal exams unless necessary.

- If the water breaks and the mother doesn’t go into labor for too long, risk of infection is higher. Digital vaginal exams increase the risk of infection.

- Inducing labor with pitocin induces stronger contractions and may make it harder to go without an epidural.

- I will drink water during labor.

- Doctors fear gastric aspiration, where patients under general anesthesia (historically used for C-sections) vomit and inhale solids into the lungs and suffocate.

- However, nowadays C-sections are performed with local anesthesia 90% of the time. And the risk of maternal death from aspiration is 2 in 10 million births, or 0.2% of all maternal deaths.

- Regardless, most hospitals will still prohibit solid foods.

- Gatorade during labor reduces maternal ketosis.

- Our doula will be with us.

- Doulas are birth companions who accompany the mother throughout the labor process, keeping a relaxed atmosphere and suggesting changes like walking around. They also give a postpartum visit.

- Research shows doulas reduce risk of C-section by half and reduce use of an epidural or forceps in delivery.

- Oster thinks having one was one of her best pregnancy decisions.

- Monitoring should be done intermittently or mobile, not continuous or immobilized.

- Doctors want to track fetal heart rate to detect fetal distress. >85% of women have monitoring during labor.

- Options for type of monitoring include immobilizing monitoring, portable monitoring, or an internal monitor (that’s threaded through the cervix and screwed into the baby’s scalp).

- Options for style of monitoring include continuous, or intermittent listening.

- Continuous monitoring leads to much more intervention, increasing C-section risk by 60% and use of instruments, but without any difference in baby outcomes (APGAR scores, NICU admissions). Oster argues this is because continuous monitoring leads to false positives about fetal distress.

- Some hospitals may have a non-negotiable policy on monitoring.

- If labor progression is slow, we prefer augmentation by amniotomy (breaking water) first, then Pitocin.

- Both interventions generally don’t have other complications like increasing risk of C-section.

- Oster preferred Pitocin last because of increased pain in labor and increased risk of C-section.

- No routine episiotomy.

- An episiotomy is cutting the perineum between the vagina and the anus. The logic goes, if there’s a controlled cut there, we can control the tearing.

- However, Oster uses the analogy of ripping a cloth in half - is it easier on an intact cloth or one that already has a rip?

- This used to be common, used in 60% of births in 1979. However, studies showed increased bleeding and slower healing, and so episiotomies dropped to 25% by 2004.

- This is useful to check with your OB well ahead of time in case there are large philosophical differences.

- Pitocin in the 3rd stage is fine if necessary/recommended.

- Pitocin reduces risk of severe blood loss after labor. However, it also increases maternal blood pressure, pain after birth, and vomiting.

Chapter 21: The Aftermath

The baby’s out! Now there are just a few more actions to know about.

Delayed Cord Clamping

- Waiting a few minutes to cut the cord allows the baby to reabsorb some blood from the placenta.

- This is useful for premature birth, halving the need for blood transfusions for anemia and hypotension.

- The risks are mixed for full-term babies, as they get higher iron levels but also risk jaundice.

Vitamin K Shots

- They’re meant to reduce bleeding disorders.

- These have been standard since the 1960s.

- Some controversy has arisen about its linkage to childhood cancer, but these findings were not replicated. Common sense suggests that if vitamin K did cause cancer, cancer rates should have increased in the 1960s when they became standard.

Antibiotics in the Eye

- Gonorrhea or chlamydia exposure to the baby during birth can lead to blindness.

- It’s mandatory in most states even if you don’t have STDs. But there’s no real downside to them.

Cord-Blood Storage

- The idea is stem cells from cord blood can be useful for treatment.

- Families with severe rare blood disorders may find this useful.

- Putatively this is useful for bone marrow transplants for leukemia. However, keep in mind a child cannot use her own cord blood; she must use a sibling’s. The chance of using banked cord blood is 1 in 20,000.

- Another sales pitch is that cord blood could be used for regenerative medicine in the future. Oster argues that by that point, we’ll probably have better stem cell technologies in general, including techniques to derive stem cells from ordinary cells.

- Consider banking in a public blood bank instead to help a stranger out.

Chapter 22: Home Birth

<1% of women in the US have a home birth. If you’re high risk (breech, twins, gestational diabetes), you’ll probably need a hospital birth, as it’ll be hard to find a midwife to attend a risky birth.

Home birth supporters will say that delivering at home is how it’s been traditionally done. It’s more comfortable, and you don’t risk the hospital forcing you to get a treatment you don’t want. Studies also show that births at home show fewer vaginal tears and lower infection rates.

In contrast, hospitals are useful for interventions - emergency C-sections, Pitocin to reduce hemorrhage, epidurals, doctors who have seen plenty of unique birth situations before.

Research is mixed on infant death and outcomes on home birth vs hospital birth.

Up to a third of mothers planning first-time home births change their mind during labor and deliver in the hospital. This abrupt transition will probably be more disruptive than starting in the hospital.

If you do choose home birth, Oster suggests working with a certified nurse-midwife, who will have the most training and certification. Certified professional midwives don’t have a nursing degree, and direct entry midwives don’t have a college degree and no license.

A good compromise - your hospital may have a more comfortable birthing center, a comfier room with a tub, a bigger bed, and less fetal monitoring.